Human Computer Integration Lab

Computer Science Department, University of Chicago

Essays (long-form writings from our lab)

(Back to all essays)Essay #1: Ask-me-anything at UIST 2022 about "Being a new faculty/starting a new lab" by Prof. Pedro Lopes

28th October, 2023

TLDR: At the ACM UIST 2022 conference I was humbled by being invited

to give a special Ask-Me-Anything talk about my experience of starting on

the tenure track and starting a new lab. Recently, I was immensely moved by the

support of my colleagues at the University of Chicago's Computer Science

Department who granted me early tenure in July 2023. This whole tenure

adventure, plus the fact that UIST 2023 is starting now, motivated me to finally1

summarize my AMA for those who were not able to attend UIST 2022—many of whom

wrote me or the UIST 2022 Social Chairs asking if the AMA would be publicly

available—happy to say that despite how it makes me nervous to share this

online0, it now is available and you can watch the first half of the AMA here (25 minutes with slides).

(Click on the image or here to watch the talk)

An…AMA?

For those unfamiliar with the acronym, AMA stands for Ask-Me-Anything—a

format in which audience members can ask questions to the speaker on a given

topic. This format, which started as interactive discussions on social media

platforms such as Reddit, become immensely popular in the media in recent years2.

What is worth emphasizing is that the AMA is a way to instigate authenticity on

subjects we might not always talk about.

Subjects that we-do-not-often-talk-about are plentiful in academia,

from the lack of diversity & inclusion to the many unwritten rules of

hiring—just to cite a few. Fortunately, in the past years, the culture in

academia seems to be changing to one that more openly discusses many of these

previously unspoken questions—you can see this change in the way researchers

discuss hard questions of academic life in social media & podcasts3.

Pushing this openness forward, I was thrilled that the ACM UIST (possibly my

favorite conference4) has taken valuable time from its busy

program to openly explore some of these hidden parts of academia with its

audience, allowing researchers to ask questions to one another on topics

such as applying for the HCI job market (AMA with Prof. Stefanie Mueller5),

conceptualizing a thesis statement (AMA with Prof. Wendy Mackay6),

to the challenges of setting a multidisciplinary research agenda (AMA with

Prof. Lining Yao7).

AMA: "Being a new faculty & starting a new lab"

This brings us to the AMA

session I was invited to give at UIST on "Being a new faculty &

starting a new lab". Together with the Social Chairs at UIST 2022, we

decided that it would be best to do this in two parts: (1) an initial talk with slides, where I

would summarize who I am and my experience as a tenure-track faculty in the US

for four years; and, (2) the actual Ask-Me-Anything section where I

tried-my-best-to-give-folks-useful-answers. You can watch the first part on YouTube (courtesy of

Donald Degraen10 and Kashyap Todi11). Before I dive into

details about the talk, I want to clarify why the second part (i.e., the actual

Ask-Me-Anything) was not recorded. The organizers and I talked about it

and felt it would prevent the AMA from being a mechanism for an open

discussion; in other words, recording could make some shy away from asking

their important questions12.

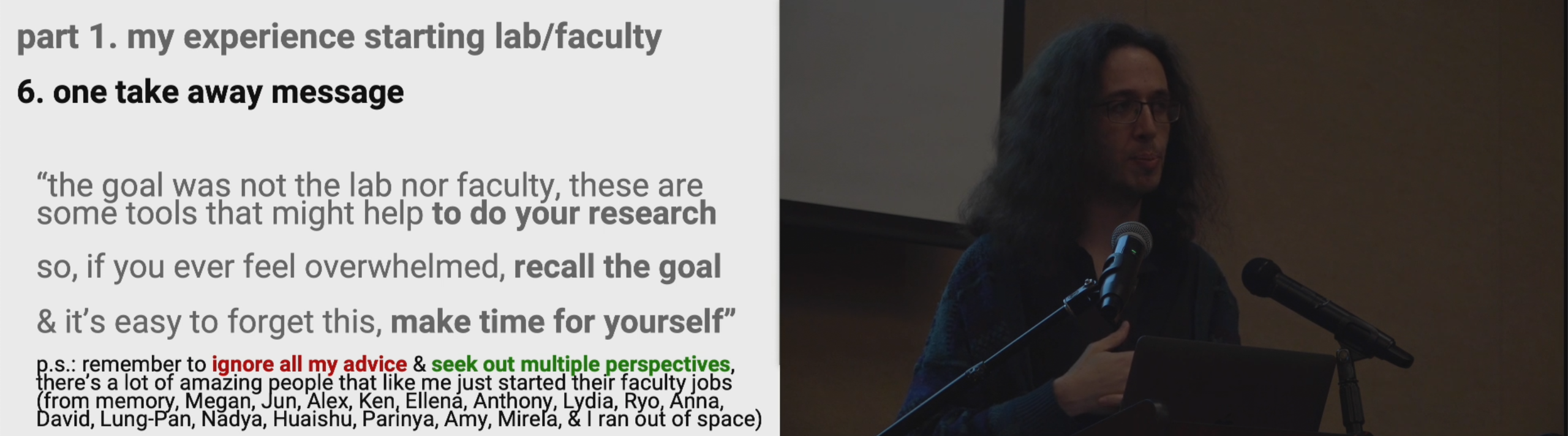

1st takeaway from my AMA: find your style. It matters.

The main takeaway from this AMA was to find your own

style. Running a lab or starting a faculty job will be much more

interesting and joyful if you do it according to your style.

This might be where my advice departs from what people told me they read online. There are many guides for success filled with technical details and productivity tricks, such as Reddit posts, Quora questions, popular books, and also the insightful advice of exceptionally successful researchers in our field (e.g., Prof. Amy J. Ko’s incredible essays, many of which also dive into personal experiences with tenure and the hidden sides of being a professor, or Prof. Phillip Guo’s great notes on the tenure-track—just to cite a few). With all these exceptional detailed sets of advice already online, I opted to emphasize something that I think does not get enough discussion: finding your own style.

I hope you are critically saying back to me: “Starting

by thinking about style? Shouldn’t I start by doing what successful people in

my field did?”. Let me argue against this for a second and then I will end

by arguing for it too, as a way to bring both sides together.

Finding your style will bring you joy every day. This matters because faculty work takes place every day—not just on the day you get that incredible result in an experiment or an award. It happens every weekday and it can entail an astonishing level of multitasking. Devoting yourself to all these numerous tasks in a way that does not bring you joy and/or does not align with your inner self (your principles & core beliefs) may feel out of place.

Instead, I argue that being a new faculty and running your lab in your own style will feel much more enjoyable—I do not use this word lightly, I think joy is also an important part of why many do research.

Most pieces of advice that you have been given (my advice

included) are well-intentioned, but cannot be empirically proven13,

i.e., what parts of my advice contributed to any kind of actual success will

remain a mystery to me. There are ample reasons for chance and a million of

other factors to have contributed more than any advice I would try to single

out. Importantly, in the AMA, I was not arguing that we should not embrace the

advice of others (as an advisor to six PhD students, I believe a lot in

giving advice). Instead, the AMA tried to articulate that you might first try

advice to see how it fits your style.

Research… Style?

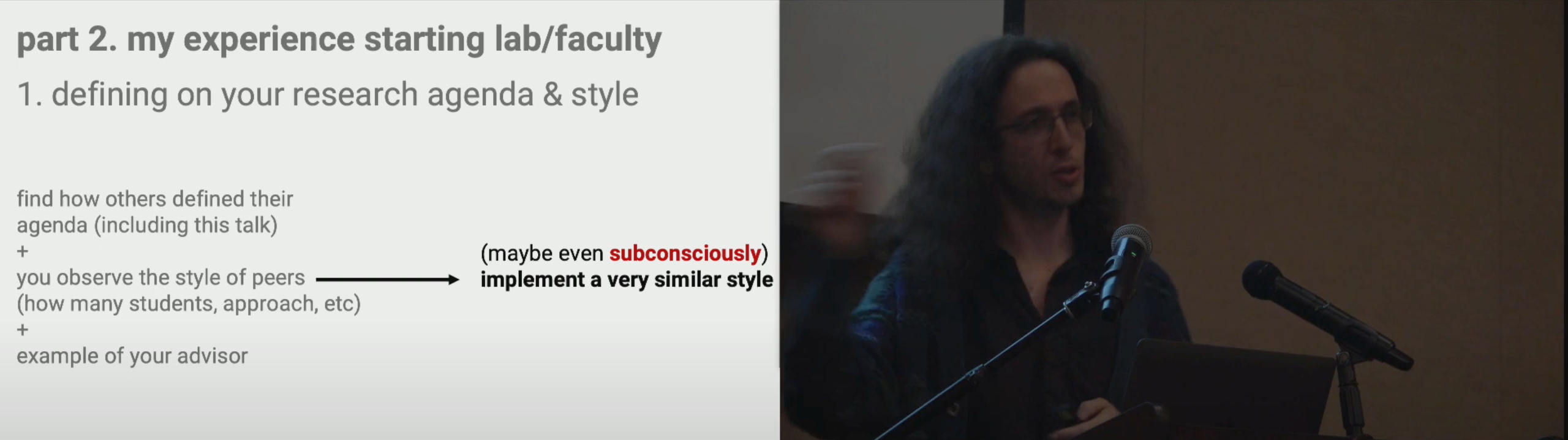

In the AMA I argued that there is a natural tendency (even

if at a subconscious level & even if motivated by great reasons) to follow

the advice of those who have been successful before us (e.g., peers, your

former advisor, a Nobel laureate on social media, and so forth). There is

nothing wrong about doing so, but you might first let yourself observe their

style after a dose of self-reflection. Otherwise, you might, even if

subconsciously, implement a style that might not entirely fit you.

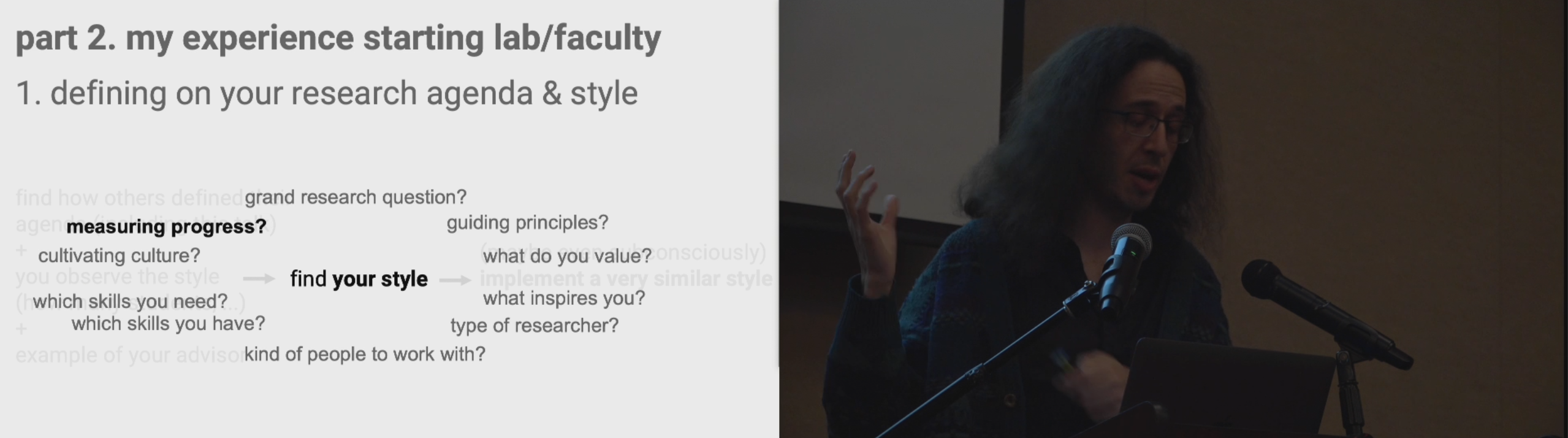

What I argued in the AMA was that to find your style, you

need to first examine your guiding principles. These are the

reasons why you are starting a lab & starting an your

academic job. This exercise, which might seem too simplistic at first, takes an

enormous amount of time & energy. You need to sit there all by yourself and

answer: why do I really want to do this? Personally, I often found

myself doing things also out of sheer inertia (i.e.

because I had some momentum doing a similar thing before) and it can take a lot

of energy to halt that momentum and, instead, turn my focus somewhere else.

Guiding principles. In the AMA I discussed several questions that you might

want to ask yourself before you start your lab/faculty career.

1. Why do I really want to do this? This is an extremely personal

question but enlightening even if the answer still feels vague and partial. For

me, I found that I really wanted to find new things out about how we could

interact with computers in more embodied ways. So, understanding that my

research question was at the core of why I wanted to do this job helped me to

understand how certain aspects of my job could look like—namely, those aspects

that I was going to have control over (e.g., whom do I hire, how should I spend

my time, what type of physical lab infrastructure might we build, and more).

2. What do you value? This is potentially the most important aspect: what

are the values you believe in? Is it number of papers, kindness, or getting to

the bottom of something? As I mentioned in the AMA, I was not trying to cast a

judgment to say that any of these values are superior; instead, I was arguing

that once you know what are your values, this can guide everything you do as

faculty/lab director. For instance, if kindness is something you value, you

might find yourself actively creating opportunities for your students to

experience what a culture of kindness can do to the lab.

3. What inspires you? Understanding your sources of inspiration might

allow you to understand where your group will put a lot of its energy, such as

in terms of what fields and publications you will be examining, but also to

which fields and publications, you will be hoping to impart your insights onto.

If you never discuss with your group where your inspiration comes from, there

is a chance that your students might assume it comes from one source

exclusively, which could devalue important sources of inspiration for everyone.

For instance, in my case, I take as much inspiration from HCI papers as I take

from artworks or neuroscience. I noticed that my group often shares with each

other references that we think others might be inspired by, and looking at our

#related-work channel there is quite a bit of art, neuroscience,

sustainability, chemical sciences, and material sciences being shared—all of

which we find important in our work.

4. What type of researcher are you? This was a really difficult one for

me to reflect on since it can often come down to asking what kind of person you

are too. This helped me understand questions such as: what type of advising

style I would be comfortable executing (e.g., the iconic hands-on vs. hands-off

discussion); how much I enjoy collaborations with others or prefer my own

explorations; what research methods I want to employ right now (note that like

anything in these lists, these aspects change as one evolves—more on this

later); and much more.

5. Which skills do you have & need? When you set up a lab, you

contribute by teaching your skills to your students; conversely, they will contribute

back to the lab by sharing their skills. This is an opportunity for you to

think about what skills you would like everyone to be exposed to in your lab,

or even what skills might they bring to the lab that will greatly advance the

way you investigate questions that matter to you.

6. Cultivating culture. A research lab is an organism and it needs

cultivation & active care. If you start a group without thinking of the set

of values that are important to you, you risk that it might be very hard to

impart those at a later stage of the lab, once other values have settled in.

This is not to say that you can decide what a group of people will think (from

my experience, you certainly cannot) but you can cultivate & cherish values

that you think will be important to achieve your lab’s potential.

7. Measuring progress. Finally, you have now set up a whole group of

people, according to your guiding principles, and started running this lab.

But, how do you measure its progress? How do you know if the lab is doing well?

As I mentioned in the AMA, I find this question very difficult but, to me, it

returns to your values, which you now also use as metrics to validate

progress. In my case, I measure progress by the amount of creativity that we

generate, rather than by our everyday productivity.

Finding answers to these questions before I

started my lab allowed me to better understand what my style might look

like. With some of this in mind, I think I was able to better adopt or not the

advice of others—based on whether it might fit my style. In fact, I have heard

many amazing pieces of advice that I either never incorporated (i.e., I could

see ahead they did not fit my style) or, even, that I tried for some time and

stopped (i.e., I was able to see after trying that they did not fit my style).

One research style for life? No. I want to add a word of caution of

course with my metaphor of style. I purposefully used the gerund of

find: finding your style. This was meant to signal that

you will be finding your style over and over again. It probably will not

change every day but, will evolve as you evolve as a researcher. As I tell my

undergraduate students, as researchers we are comfortable doing the same thing

over and over—after all it is not called search, it is called research.

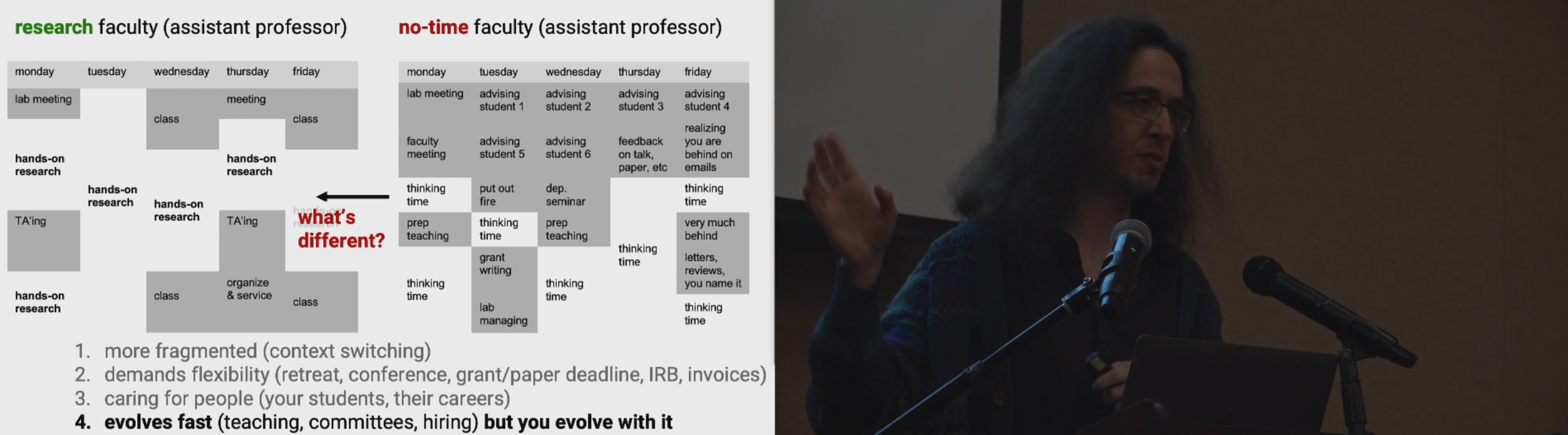

2nd takeaway from my AMA: make time for yourself

The second focus of the AMA’s first part (the public

lecture that is on YouTube) was how

difficult the transition from PhD14 to faculty can be.

One of the aspects that I think are the hardest to get used to when becoming faculty is how your day looks like. Prof. Amy J. Ko’s excellent essays page, which I alluded to earlier, has a fantastic piece demonstrating the level of multitasking that a professor might do on a single day (from teaching to advising, to funding, to service, to everything else one does in life, including parenting). As a new faculty, the number of moving goalposts that you might have to start wrestling with might feel overwhelming—not to say a PhD. is easy, but there are fewer responsibilities to juggle. You might start finding it hard to go through a to-do list compromised of a single time-sensitive item. However, as the days go by in your newly appointed faculty job, this level of busyness can become ingrained. This is both OK and extremely bad. It is OK in that you get better and, thus, not so easily overwhelmed. However, this is extremely bad in that it becomes far too easy to be so overworked with days full of back-to-back meetings that you forget: “Why do I really want to do this?” (which was our guiding principle #1).

Instead, I often found that having done that (now seemingly

simplistic) exercise of finding my own style (i.e., knowing my guiding

principles) I could better remind myself of why I was doing all this. This not

only greatly helps on challenging days but also when you find that you need to reverse

course so that you better dedicate yourself to whatever reason you answered

in step #1.

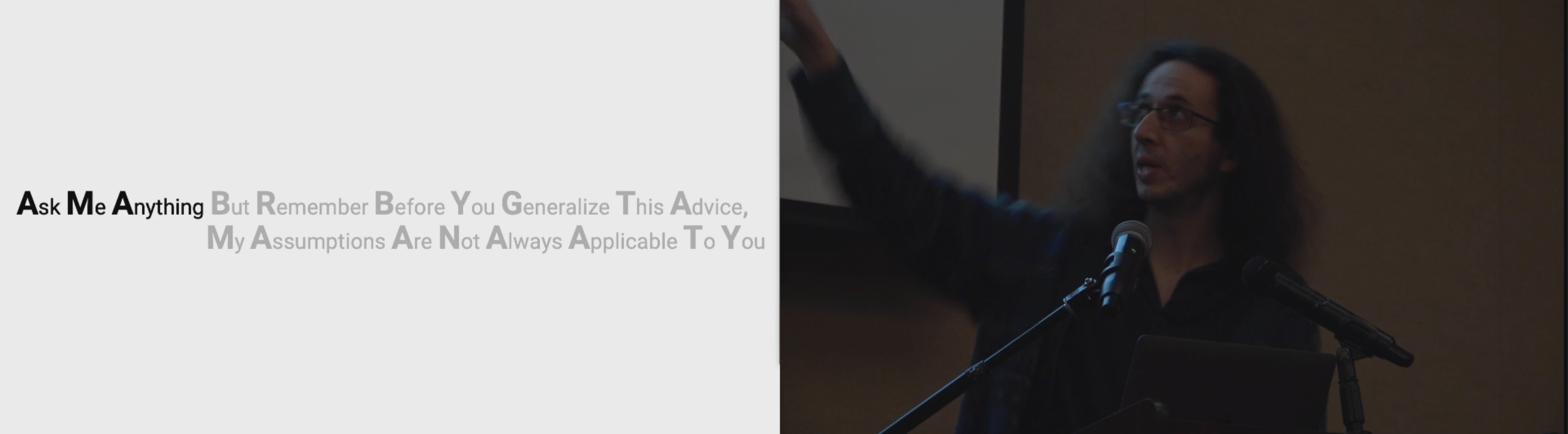

While in my AMA I fought very hard to not give any advice

that sounded generalizable (because as I mentioned in my first slides, I really

did not think of this as an AMA but as an AMA BRB YGT AMA ANA ATY—Ask Me

Anything But Remember Before You Generalize This

Advice My Assumptions Are Not Always Applicable To You), I did venture one that

I might urge you to try it: make time for yourself15. While I

mean this in the context of what you do on your own self-appointed research

time (i.e., the hours you dedicate to work and not the hours outside of it),

making time has a positive impact also on time outside of work and can be

important to protect you from feeling overworked or feeling burnout.

Finally, I discussed four other aspects of the faculty

day-to-day schedule that were challenging for me: (1) fragmentation—a

lot of rapid context-switching between meetings or between

service/teaching/research, which one needs to either be good at (not my case)

or find ways to alleviate (e.g., by making more time for yourself); (2) demands

flexibility—what is often advertised as one of the great advantages of an

academic job (true!) can also be a demand to some extent, i.e., it

demands that you can rapidly accommodate to new schedules (e.g., every quarter

I teach a new class with a new schedule) and plan around shifting situations

(e.g., a grant is accepted, bringing new funding but also extra administrative

work; a paper is accepted, bringing great joy to share those results but also

more work with revisions & talks; you were invited to a new committee,

bringing new positive changes but also more service work, etc.); (3) caring

for students—the biggest part of my job is caring for the career my PhD

students, while this is obviously something I do joyfully it can also be

overwhelming and will often leave me zero time to think of my own career or

other aspects of my research questions; (4) evolves fast—the faculty

schedule evolves extremely fast (e.g., what my schedule looked like in year one

and year two were wildly different, luckily you also evolve with it, making a

task that used to be hard much easier the second time).

What’s up with the positive outlook on academia?

In the last part of my public segment of the AMA, I showed this equation:

faculty-fun = PhD-fun x 103

After the AMA several people asked if I really meant

an order of magnitude more fun? I really did. I really enjoyed my PhD16

and felt it was a lot of fun to explore a topic deeply and learn new skills

(e.g., electronics, user studies, and writing papers—all things I had not done

much until the PhD). However, with my lab, I get to do much more. Each of my

students explores a new topic with me and teaches me new an astonishing number

of new techniques17, I do more research with them than I used to

alone, and I get to be around more inspiring people every day (brilliant

students & brilliant faculty colleagues). This is the most joyful job I

could imagine, even when I account for all the parts I might dislike. This is not to say we should not share ways in which we think we can and should do better in academia, hopefully paving a way to fix many of the outstanding problems18. Yet, I also think it is important to share if you feel joyful about your job.

Post-script: why I focused on these topics?

This was maybe the oddest talk I had the pleasure of

giving. Mostly because it was not about my research—I spent only 2 minutes and

35 seconds on my research at the start just to give some context of which

research field I am coming from, since I felt that also carries some contextual

cues and biases to my perspective.

I wrote this talk from personal reflection, looking back (digging through my calendar & emails between 2019-2021 to see what was most challenging in my new job), and by talking to colleagues during the first three days of the UIST conference (thanks everyone who talked to me about it)—I remember being at the opening reception and bumping into colleagues who, like me, were also on the first years of their first academic job. All of them were extremely kind to provide questions or stories for the talk. While I knew I could only tell my story and not theirs, I noticed how many of their questions I could boil down to find your own style—which is how this became a central part of the talk.

Other topics that they mentioned were on the back of my

mind too, and after hearing their stories I pushed them to the foreground. One

such topic was the abrupt change from previous positions (e.g., from PhD) to

one with new responsibilities (e.g., assistant professor). As you can see in

the AMA, I dedicated a sizable amount of time to this topic—one year later, I'm

glad I did that, many came to talk to me about it right after the AMA and had

even more great questions about this. That being said, there were many topics

that I collected from colleagues that never made it into the short talk, nor

appeared in the 1h discussion that followed (the actual AMA part) and they

deserve as much attention as the topics we did bring up. Some of these topics

include: finding students to work with, hands-on vs. off advising, emotional aspects of the job,

setting up a lab infrastructure, knowledge transfer inside the lab, collaborations, teaching

load, budget, grants, space, committee and department service, running a lab in

the pandemic, and more.

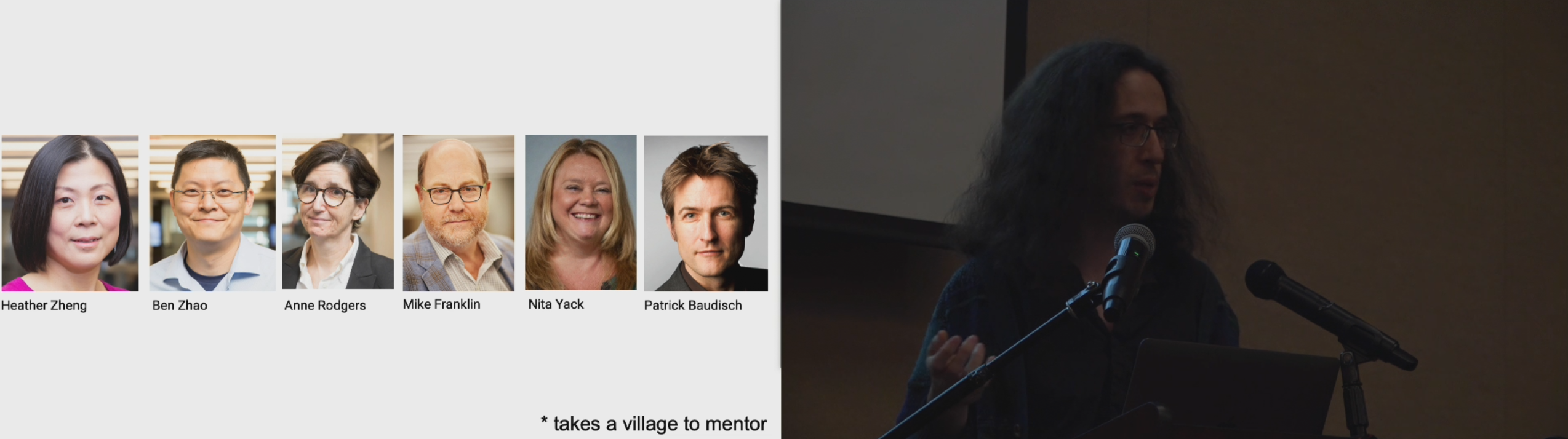

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the ACM UIST Social Chairs 2022 for inviting me and trusting me with this AMA, I can only hope they did not regret this decision!

Secondly, I would like to repeat my acknowledgment slide,

which only included a small number of the large number of people at the

University of Chicago and beyond who helped me in my first years.

Absent from it is my friend Prof. Blase Ur,

who I cannot thank only academically because he also helped me with everything

else in my life in Chicago—thank you!

Footnotes

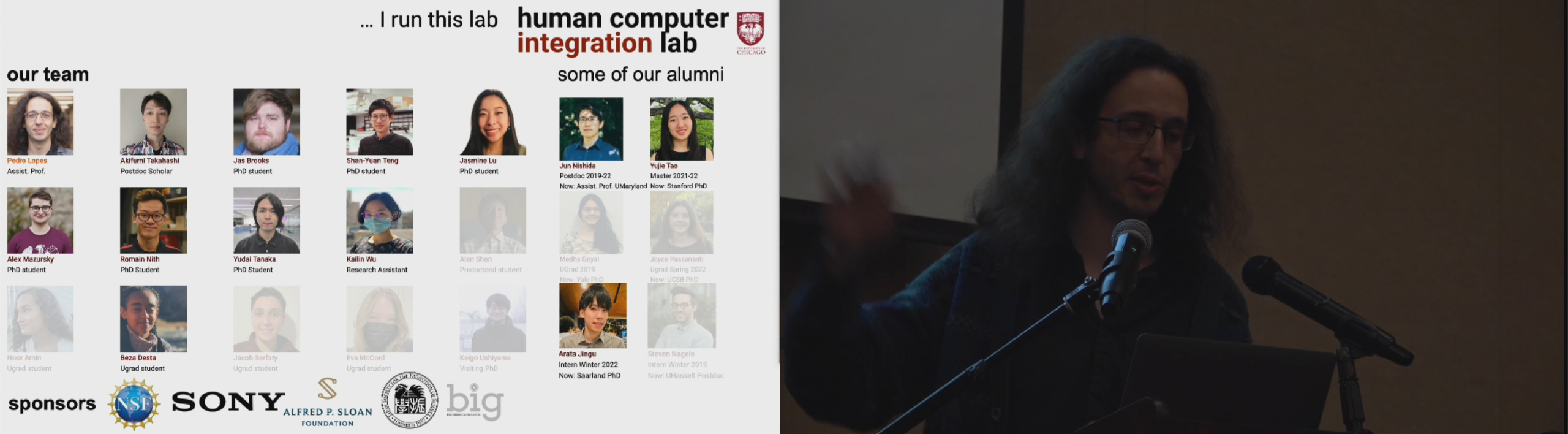

0 There were so many mental barriers to giving this talk. At the top of

the list was a wish to share some insights but to, also, not come across as preaching

like my advice was special in any way (it is not).

Secondly, twelve of my students were in

the audience. This was hard because no matter what I would say, it was about

“starting a lab”—their lab. While the talk portion did not contain much that they

could be embarrassed by, I knew the actual AMA part (the hour of discussion that followed) would be more personal—it was. There were questions were I had to highlight some story or experience that was

about one of them. I thank them for coming along to the talk and supporting me

as they always do. Below is a photo of

my team at that time and the highlight of everyone who was there at the talk,

which included: Akifumi

Takahashi (postdoc), Jas Brooks (PhD),

Shan-Yuan Teng (PhD), Jasmine Lu (PhD), Alex Mazursky (PhD), Romain Nith (PhD),

Yudai Tanaka (PhD),

and also Alumni, K. D. Wu (RA at the time), Beza

Desta (undergraduate at the time, now Princeton PhD); Prof. Jun Nishida (previously

Postdoc, now Assistant Professor at Maryland), Yujie

Tao (previously Master student, now Stanford PhD) and Arata Jingu

(previously summer intern, now Saarland PhD).

1 I say finally because, indeed, it took me a year to write this

up. I could blame it on the fact that 2023 was a strange year for me, riddled

with challenges such as health condition (of which I can’t say I truly escaped

but more that it seems like I’ll survive this round, win!) and, of course,

doing all the challenging research that brings me joy. But it took me a year

because, just like the AMA talk itself, these public reflections do not come

naturally to me, even with all the lovely feedback from those who said that the

AMA helped them already—thanks for saying that and for pushing me to write

this.

2 The Atlantic wrote a piece

about the genealogy of AMAs if you are curious to learn more.

3 If you are looking for the latter, I'd like to use this opportunity to

highlight the spectacular work of Prof. Geraldine

Fitzpatrick with her podcast Changing Academic Life, which

is available wherever you get your podcasts atTM—in it, she addresses many

of these difficult challenges with academia and academic life in general; it’s

incredible.

4 Turns out choosing a favorite conference is not as easy as I initially thought, but suffice it to say that no matter what side of the bed I wake up every morning, ACM UIST is solidly among my top choices.

5 I do not know if Prof. Stefanie Mueller’s AMA (“Applying for Faculty Positions”) was recorded or is available—you can find the information at the UIST 2021 website—but our lab listened to it together and we were all very much inspired by her wisdom. While I cannot speak for her, I am certain that if you ask her9 more about her experience you might receive great advice from her; I know I have on several occasions during my PhD.

6 I also do not know if Prof. Wendy Mackay’s AMA (“How to Design Your Thesis Statement”) was recorded or is available—you can find the information on UIST 2021 website—but I learned so much from her by listening to her perspective & experience (I was lucky to serve several time alongside her in several CHI/UIST PC meetings, including my very first one in-person) that I would highly recommend you ask her for her advice9 on thesis or anything UIST-related!

7 This is a string of I-don’t-know’s, but, indeed, I also do not know if Prof. Lining Yao’s AMA (“Doing antidisciplinary research”) was recorded or is available—you can find the information on the UIST 2022 website—but I sat in this talk and learned a lot. Those who know me will not be surprised by this, since I think Prof. Yao is an incredible researcher when it comes to creative energy that exceeds all boundaries of fields, so she is definitely someone you should ask9 about doing multidisciplinary research.

9 (I know references inside of references feel like Infinite Jest.) What is very special about UIST and Human-Computer Interaction is that while Prof. Stefanie Mueller, Prof. Wendy Mackay & Prof. Lining Yao are absolute stars in this field, they are also usually at UIST and many other conferences, so you can just ask them for advice! I found that researchers in our field are extremely open & kind to offering their advice to you.

10 Donald Degraen is an exceptional researcher working at the intersection of haptics, fabrication, and virtual reality, you should check his work out if you are interested in this area. He also served as the UIST 2021 Social Chair and invited me to give the AMA talk.

11 Kashyap Todi is an exceptional researcher pushing the boundaries of HCI and computational methods, (Kashyap has been doing the HCI+AI before it was a hype!), you should check out his work if you are interested in this area. He served as the SIGCHI Video Operations Committee Member and was kind enough to provide me with the video recording of my AMA talk, so it is all thanks to him that we can have this on YouTube. Also, I would like to use this opportunity to also thank Kashyap for maintaining a lot of knowledge in our community, such as the lovely what the HCI website.

12 Perhaps you, personally, might not feel like this, but many might feel pressure from being “on-camera” or “recorded for posterity”. As a teacher who has recorded some lectures for those who could not be there (e.g., during pandemics—with the consent of students), I have seen this: many feel more at ease to ask any questions, especially difficult ones when they are not on camera. We wanted this spirit for UIST 2022’s AMAs.

13 That is what makes these topics so hard and so susceptible to survivorship bias. Nobody can run an ethically-sound experiment on themselves and their group to deeply investigate which factors contribute to success—and even that experiment is likely not possible, given the complexity of the social structures involved and the inability to time-travel or instantiate a perfectly parallel reality. Thus, I am not trying to discredit the insights of others, in fact, I am suggesting that openly discussing this is the best we have.

14 Note that I did not do a postdoc and the transition to faculty might look different to those who did. In fact, the reason why my AMA started with a very brief overview of my path was to clarify how my trajectory went and also what type of work I do—this also has an impact on many of my advices since they might not make sense in the framework of somehow that, for instance, does not need to manage a physical lab full of machinery.

15 In the AMA I gave some examples of how I tried to free some of my time, which I did not go into detail here but included: trusting my students to undertake tasks that I was initially doing alone, asking colleagues for help, using available recourses (e.g., teaching relief—which I did not use and was a mistake in hindsight), and planning ahead when possible.

16 I was also really lucky to be able to do my PhD with an advisor, Prof. Patrick Baudisch, who gave me a lot of space to explore a topic that was new to the two of us. He also would buy me an espresso when I most needed to relax, e.g., while stressing about the job market or after my first faculty interview. While I am immensely grateful for all of it, I think he will not take it to heart that my equation says that faculty-fun so far is an order of magnitude greater than my PhD-fun was.

17 I have learned about pharmacology from Jas Brooks, about sustainability from Jasmine Lu, about neuroscience from Yudai Tanaka, about mechanics from Alex Mazursky, about electronics from Romain Nith, and about prototyping from Shan-Yuan Teng—just to cite one of many aspects I have learned from each of my PhDs; the same goes for learning from our postdocs, undergrads, and high-schoolers.

18I had many students telling me that "being a professor can only be horrible because of what they see on Twitter (namely #AcademicTwitter)". Again, this is not to say we should not share stories, personal experiences, grievances, and ways in which we think we can and should do better in academia—there are a lot of systemic issues that affect disproportionally a lot of people in academia (I'd like to note I am in a privileged position at the University of Chicago). Yet, hopefully, there is a way to share these grievances and form a community online to support each other (e.g., at #AcademicTwitter and hopefully in many virtual and physical spaces) and, simultaneously, share when you feel joyful about your academic job.